Am I allowed to conclude "Trust-based Philanthropy" is misguided yet?

Evidence-based giving shouldn't be optional

Wait — so you’re saying you hate trust?!

"Trust-based philanthropy" sounds nice, doesn't it? After all, who could be against trust?

But here's the thing about beautiful-sounding phrases in the charity world: they often mask deeply flawed practices. And after watching MacKenzie Scott (Jeff Bezos's ex-wife) set fire to $17 billion in the last five years – nearly three times what the entire Rockefeller Foundation has to give away – I think it's time we had an honest conversation about it.

For those unfamiliar, trust-based philanthropy is an increasingly popular approach based on the idea that non-profits know better than wealthy donors how to serve their beneficiaries, so funders should simply let the organizations themselves decide how money gets spent. This typically means minimal oversight, reporting requirements, or restrictions on how funds can be used.

The goals behind this movement are admirable: reduce unnecessary bureaucracy, respect the expertise of people closest to the problems, and build more equitable relationships between funders and grantees. I've seen trust-based funders do excellent work, particularly in the movement against factory farming. But what sounds like admirable humility often becomes a dangerous abdication of responsibility.

Here's a way to understand why: Imagine if Warren Buffett announced he was switching to "trust-based investing." No due diligence, no analysis of returns, just vibes. He'd be laughed out of Omaha. Yet somehow, when it comes to philanthropy – where the stakes are arguably even higher, since we're talking about improving and saving lives – this approach has become trendy.

Advocates of trust-based philanthropy will say they believe in both trust and verification. But in practice, their approach emphasizes reducing oversight while offering no clear mechanism for ensuring effectiveness. They’re dismantling all verification systems while claiming to still care about results.

Some aspects of trust-based philanthropy are eminently sensible. For example,1 I agree that restricted grants (where funders dictate exactly what money can be spent on) are generally a bad idea — mainly because the restrictions are very easy for charities to evade through clever accounting. But this insight isn't unique to trust-based philanthropy — it's just common sense that many approaches share. In fact, the good parts of trust-based philanthropy aren't new, and the new parts aren't good.

The broken core of trust-based philanthropy

Trust-based philanthropy's most distinctive feature is the motivating principle that charities know best how to use money, so funders should defer to their judgment. This falls apart for several reasons. First, it's intellectually dishonest – you're not actually putting the money in a pile and letting organizations collectively decide how to allocate it. The money is finite, and someone has to choose who gets it. In trust-based philanthropy, funders are still making that choice – they're just doing it based on intuition rather than evidence.

More troublingly, while trust-based philanthropy claims to shift power from wealthy funders to practitioners who better understand the problems they're trying to solve, it often has the opposite effect. In practice, it becomes a way for philanthropists to give based on gut feelings and personal relationships rather than doing the hard work of analyzing evidence and giving where resources will do the most good – even when that's not the most emotionally satisfying choice. Ironically, this gives funders more power than ever, as they're no longer even accountable to showing their decisions are well thought through and backed by evidence.

MacKenzie Scott exemplifies this approach. Since 2020, she's been trying to get rid of her share of the Bezos fortune like the money is haunted, having given away an eye-watering $17 billion. Organizations often receive multi-million dollar donations completely out of the blue – so unexpectedly that some initially mistake the notification emails for spam. When you dig into Scott's essays about her philanthropy, you find flowery (and IMO self-righteous) language about equity and empowerment, but zero discussion of actual impact. Her communications overflow with beautiful words about intentions while remaining conspicuously silent about results.

Singling out Scott might seem like I'm attacking a 'strawman' version of trust-based philanthropy, but in my experience, the only thing special about Scott is how quickly she's deploying her funding (for which I commend her – there's no virtue in milking your endowment for over a century like Rockefeller).

Whenever anyone criticizes this approach, defenders rush to explain that we're misunderstanding "true" trust-based philanthropy. Just last year, the Stanford Social Innovation Review published a spirited defense arguing that trust-based philanthropy can actually be highly strategic if done right. They paint a compelling picture: organizations responding quickly to emerging needs, spending less time on paperwork and more time on impact, leveraging their deep understanding of local contexts.

But this defense falls into a classic logical trap known as the "No True Scotsman" fallacy. The pattern goes like this:

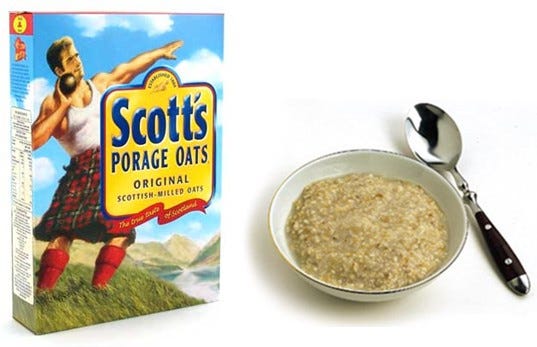

Someone says "No true Scotsman puts sugar in his porridge."

When presented with Angus, who definitely puts sugar in his porridge, they respond..

"Well, Angus isn't a true Scotsman."

Similarly: "Trust-based philanthropy, when practiced correctly, is strategic and impactful!" → "But look at all these funders just throwing money around based on vibes!" → "Well, that's not true trust-based philanthropy..."

At some point, we have to judge ideas by how they work in practice, not by their platonic ideal. If virtually no one manages to implement "true" trust-based philanthropy – if it almost always devolves into giving money based on gut feelings and hoping for the best – then maybe the approach itself is fundamentally flawed.

This matters enormously because the stakes are so high. Every dollar squandered is a dollar not spent on actually helping people. When we prioritize donor feelings ("It feels so good to trust!") over actual impact, we're prioritizing our own emotional comfort over the needs of those we claim to serve.

Don't get me wrong – I'm all for reducing unnecessary bureaucracy in philanthropy. The solution to "some oversight is unnecessary" isn't "therefore no oversight is best." The solution is to thoughtfully determine what oversight actually drives impact. We can streamline processes without abandoning accountability. We can respect expertise while still measuring results. We can build genuine partnerships with grantees that neither micromanage nor neglect proper oversight.

But first, we need to be willing to say what many are thinking but not enough are saying: Trust-based philanthropy might be great in theory, but in practice, it's just an excuse to give based on vibes.

Some other aspects I agree with, which I’m relegating to the footnotes as people mostly want to hear the criticisms:

I agree with trust-based philanthropy that reporting requirements should be minimized: (a) Funders should only ask for reporting that is decision-relevant for them, (b) The amount of time it takes charities to do the reporting should be in proportion with the amount of funding — I was once asked for detailed reporting from an funder who granted my non-profit $1000. (c) Wherever possible, funders should ask charities to share performance reporting they would already be collating anyway for internal purposes or for other funders, to avoid charities spending weeks collating 10 bespoke reports for their different funders.

I also agree with trust-based philanthropy that charity practitioners have a unique and valuable vantage point by virtue of working directly on the problem. But so do funders, who get to see patterns in what does and doesn’t work across dozens of charities using different tactics to tackle the same problems! The appropriate course-correction for funder who haven’t been listening to practitioners isn’t to throw out the funder’s perspective entirely and do whatever the charities want — it’s to combine both perspectives, factoring in their comparative advantages, to make better decisions than either group could alone.

Dear Aiden,

I must disagree, as your argument is based on misconceptions about Trust-Based Philanthropy. (Indeed, it’s the same false narrative commonly circulated about TBP.) Having worked in the funding space for 15 years and implemented various approaches, I can confidently say that, from my observations, TBP has been the most effective.

TBP is not giving based “vibes,” blind trust, and no accountability. At its core, TBP is about:

>Having humility to acknowledge that funders aren’t always the experts

>Actively working to dismantle power dynamics to build authentic, trusting relationships

>Which in turn enables honest dialogue with grantees so that funders can learn the reality of the work & not simply be told what the grantees think we want to hear

>Doing the extra work to develop a nuanced understanding of grantees’ strategy & not basing decisions only on cost-benefit analyses from numbers on an application

>Understanding structural racism, power-dynamics, equity and how these effect funding decisions and grantee impact.

Here are other false narratives in your argument:

*No due diligence or evidence – false.

*No impact measurement – false.

*No oversight – false.

*Based on “feel good vibes” – false.

Let me share concrete examples of TPB impact from my own work as a TBP practitioner. Prior to Thrive, I was leading (what we believe) was the largest non-USA plant-based food systems grant pool from a TBP lens. This started nearly 10 years ago when the movement was a fraction of its current size, and through this I was able to significantly expand the movement in over 70 countries, many countries which previously did not have a formal movement. In fact-several of the non-USA organizations today started as a result of this TBP work.

With Thrive, we are growing this foundational work –all through TBP. We are supporting the growth of the movement in over 80 countries & 6 continents & have the largest movement-building project across Africa. And we do all of this with clear strategy, a rigorous due diligence, metric-based selection process, and impact evaluations. Thrive also has one of the largest Board of Directors in the plant-based movement funding space – most of whom were drawn to Thrive for our TBP approach. Our decisions are certainly not made based on “feel good vibes” and we certainly must hold ourselves accountable to our own foundation partners & donors. We are transparent in our impact, as shown on our website.

While I respect your right to your opinion, I encourage you to do the work to develop a sound understanding of TBP before drawing conclusions & making a public argument against it. Perpetuating misconceptions about TBP (or any approach for that matter) can be dangerous & ultimately could harm the entire movement, starting with TBP grantmakers who could potentially lose donors based on false narratives, which subsequently would impact the worldwide grantees that they serve.

For anyone interested in supporting the growth of the plant-based food systems space from an equity-based, evidence-based, Trust-Based Philanthropy approach, Thrive Philanthropy is & always will be a TBP practitioner. We invite you to join us by applying for a grant, making a donation, or joining our Community Grantmaker project. We would be excited to partner with you. www.thrivephilanthropy.org